@About this App@Contributers@DeveloperACTH (Adrenocorticotropic hormone)AFP (Alpha-fetoprotein) TestingAIDS Dementia Complex (HIV)AIDS HIV InfectionAPGAR Scoring (Children)APTT and CoagulationAbacavirAbataceptAbbreviated Mental Test Score (AMTS)AbciximabAbdominal Aortic AneurysmAbdominal paracentesis for ascitesAbducent NerveAbetalipoproteinaemiaAbnormal Vaginal bleedingAcamprosateAcanthocytosisAcanthosis NigricansAcarboseAccelerated Idioventricular RhythmAcetazolamideAcetylcholine Receptor AntibodiesAcetylcholinesterase inhibitorsAchalasiaAchilles Tendon ruptureAchondroplasia (Children)AciclovirAcid maltase deficiency (Pompe disease)Acne RosaceaAcne VulgarisAcoustic Neuroma (Schwannoma)Acrodermatitis enteropathica (Children)Acromegaly and GiantismAcromio-clavicular jointActinomyces israeliAction PotentialActivated CharcoalActrapid (Insulin)Acute Abdominal Pain - Acute PeritonitisAcute Acalculous CholecystitisAcute Anaphylactoid ReactionsAcute AnaphylaxisAcute Angle Closure GlaucomaAcute AppendicitisAcute Bacterial MeningitisAcute BronchitisAcute CholangitisAcute CholecystitisAcute Colonic Pseudo-obstructionAcute Coronary Syndrome (ACS) GeneralAcute Coronary Syndrome (ACS) NSTEMI USAAcute Coronary Syndrome (ACS) STEMIAcute Coronary Syndrome (Cardiac Troponins)Acute Coronary Syndrome Grace scoreAcute DeliriumAcute Disc lesionsAcute Disseminated EncephalomyelitisAcute Diverticulitis - Diverticular diseaseAcute Dystonic ReactionAcute EncephalitisAcute Eosinophilic PneumoniaAcute EpiglottitisAcute Exacerbation of COPDAcute HepatitisAcute HydrocephalusAcute HypotensionAcute InflammationAcute Intermittent Porphyria (AIP)Acute Interstitial nephritisAcute Kidney Injury (AKI)Acute Limb IschaemiaAcute Liver FailureAcute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia (ALL)Acute MastoiditisAcute MonoarthritisAcute Myeloid Leukaemia (AML)Acute MyocarditisAcute PancreatitisAcute Pelvic Inflammatory DiseaseAcute PericarditisAcute Phase reactantsAcute PorphyriasAcute Promyelocytic LeukaemiaAcute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (Adults)Acute Retroviral Syndrome (HIV)Acute RhabdomyolysisAcute Rheumatic feverAcute Rotator cuff tearAcute Severe AsthmaAcute Severe ColitisAcute SinusitisAcute Stroke Assessment (ROSIER&NIHSS)Acute TonsilitisAcute Urinary RetentionAcute and Chronic GoutAcute and Chronic Heart FailureAcute on Chronic Liver Disease DecompensationAcutely Ill PatientAdalimumabAddenbrooke's Cognitive Examination-Revised (ACER)Addison Disease (Adrenal Insufficiency)AdefovirAdenosineAdenosine deaminase deficiencyAdhesive Capsulitis (Frozen Shoulder)Adjustment - Anxiety disordersAdrenal AntibodiesAdrenal PhysiologyAdrenaline (Epinephrine)AdrenoleukodystrophyAdrenomyeloneuropathyAdult Onset Still's DiseaseAfrican Trypanosomiasis (Sleeping sickness)Age related macular degenerationAicardi syndromeAir EmbolismAlbuminAlbumin-Protein Creatinine Ratio (PCR)Alcohol AbuseAlcohol Withdrawal (Delirium Tremens)Alcoholic (Steato)HepatitisAlcoholic KetoacidosisAldosterone PhysiologyAlendronate (Alendronic acid)AlfacalcidolAlkaline phosphatase (ALP)Alkalinisation of urineAlkaptonuriaAllergic Bronchopulmonary AspergillosisAllogeneic stem cell transplantationAllopurinolAlogliptin (Vipidia)AlopeciaAlpha FetoproteinAlpha ThalassaemiaAlpha subunit (ASU) of TSHAlpha-1 Antitrypsin (AAT) deficiencyAlport's SyndromeAlteplaseAltitude sicknessAluminium and Magnesium AntacidsAlveolar Gas EquationAlzheimer disease (Dementia)AmantadineAmenorrhoeaAmerican Trypanosomiasis (Chagas Disease)AmilorideAmino acidsAminoglycosidesAminophyllineAminosalicylatesAmiodaroneAmiodarone and Thyroid diseaseAmitriptylineAmlodipineAmmonia EncephalopathyAmnestic syndromesAmoebiasis (Entamoeba histolytica)AmoxicillinAmphetamine toxicityAmphotericin BAmpicillinAnaemia of Chronic DiseaseAnagrelideAnakinraAnal CancerAndexanet alfaAndrogen insensitivity syndromeAneurysmsAngina bullosa haemorrhagicaAngiodysplasiaAngiomyolipomaAngioneurotic OedemaAngiotensin Converting Enzyme InhibitorsAngiotensin Converting enzyme (ACE)Angular Stomatitis - CheilitisAnion GapAnkle and Foot fractures and InjuriesAnkle-Brachial pressure Index (ABPI)Ankylosing spondylitisAnorexia NervosaAntacid medicationAntepartum haemorrhageAnterior Horn Cell diseasesAnterior circulationAnti Dementia DrugsAnti-Cyclic Citrullinated Peptide (CCP) AntibodyAnti-D immunoglobulinAnti-Hu antibodiesAnti-OKT3 antibodiesAnti-RNP AntibodyAnti-Yo antibodiesAnti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA)Antibiotics for Abdominal InfectionsAnticholinergic BurdenAnticholinergic syndromeAnticipationAnticoagulation and AntithromboticsAntidiuretic hormone (Vasopressin)Antigen presenting cellsAntimicrobial ChoicesAntimuscarinic drugsAntiphospholipid syndromeAntithrombin III deficiency (AT3)Aorta anatomyAortic DissectionAortic Regurgitation (Incompetence)Aortic SclerosisAortic StenosisAortoenteric fistulaApathetic thyrotoxicosisApixabanAplastic anaemiaApomorphineAppendix Cancer TumoursApproach to Assessing Sick ChildApproach to child with Acute GastroenteritisApproach to child with respiratory DistressArnold Chiari malformationArrhythmogenic Right ventricular CardiomyopathyArtemisininsArterial Blood gas analysisArterial Pulse assessmentArterial blood gas samplingArterial vs Venous vs Other Leg UlcersArteriovenous malformationsArtery of Percheron strokeArtery-to-artery embolic strokeArtesunateAsbestos Related Lung diseaseAscites Assessment and ManagementAspergillomaAspergillus fumigatusAspirinAspirin Salicylates toxicityAssessing Abdominal PainAssessing BreathlessnessAssessing Chest PainAssessing FallsAsteatotic eczemaAsthmaAstigmatismAstrocytomasAsystoleAtaxia TelangiectasiaAtazanavirAtenololAtherosclerosisAtopic Eczema or Atopic DermatitisAtorvastatinAtracuriumAtrial Ectopic beatsAtrial Fibrillation (Chemical cardioversion)Atrial Natriuretic Peptide (ANP)Atrial fibrillation (AF)Atrial flutterAtrial myxomaAtrial septal defect (ASD)Atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardiaAtropine SulfateAutoantibodiesAutoimmune Haemolytic anaemia (AIHA)Autoimmune HepatitisAutonomic neuropathyAutosomal DominantAutosomal Dominant Polycystic kidney diseaseAutosomal RecessiveAzathioprineAzithromycinB lymphocytesBRCA genes (Familial Breast Cancer)Bacillus anthracisBacillus cereus poisoningBackpain / BackacheBaclofenBacteriaBacteroides fragilisBalanitis (Adults)Balanitis (Children)Balkan endemic nephropathy (BEN)Balsalazide (Aminosalicylate)Barrett's oesophagusBartonellaBartters syndromeBasal Cell Carcinoma (BCC)Basic Fracture managementBasilar artery thrombosisBecker Muscular dystrophyBeclometasoneBeer PotomaniaBehavioural and Psychological Symptoms of DementiaBehcet's syndromeBell's palsyBendroflumethiazide (Bendrofluazide)Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV)Benign Prostatic HyperplasiaBenign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasisBenzodiazepine ToxicityBenzodiazepinesBenzylpenicillin Sodium (Penicillin G)Berg Balance ScaleBeriplexBerylliosisBeta AgonistsBeta Blocker toxicityBeta ThalassaemiaBeta-2 MicroglobulinBeta-lactamasesBetahistine (Serc)BezafibrateBiceps ruptureBilateral adrenalectomyBiliary atresiaBilirubinBiochemical Lab valuesBisacodylBisoprololBisphosphonatesBladder CancerBladder StonesBleedingBleeding disordersBleeding due to DrugsBleomycinBlindness - global causesBlood products - Packed cells blood transfusionBlood Products - CryoprecipitateBlood Products - Fresh Frozen PlasmaBlood Products - PlateletsBlood film interpretationBlood gas valuesBloody DiarrhoeaBlotting Techniques: Gel ElectrophoresisBone Marrow TransplantationBone disease Lab resultsBone metabolism RANK RANKL OPG pathwayBone scintigraphy (Bone scan)Bordetella pertussis - Whooping coughBorrelia burgdorferiBorrelia recurrentisBotulismBrachial neuritis (neuralgic amyotrophy)Brachial plexus anatomyBrachial plexus and associated injuryBrain AbscessBrain Anatomy and functionBrain MRIBrain Natriuretic Peptide (BNP)Brain PhysiologyBrain Tumours (Cancer)Brainstem anatomyBranchial cleft cystBreast CancerBreast FibroadenomaBretyliumBroad complex TachycardiaBromocriptineBronchial adenomaBronchiectasisBronchiolitisBronchoscopyBrown-Sequard syndromeBrucellaBrugada syndromeBudd-Chiari syndromeBudesonideBuerger disease (Thromboangiitis obliterans )Bulbar vs Pseudobulbar palsyBulimia NervosaBullous PemphigoidBumetanideBunionsBuprenorphineBupropionBurkholderia cepaciaBurkitt's lymphomaBurnsBusulphan (Busulfan)ByssinosisC reactive protein (CRP)CADASILCARASILCHADS2 - CHA2DS2-VASc scoreCMV retinitisCNS fungal InfectionsCNS infectionsCSF RhinorrhoeaCT Head Basics (Stroke)CT Pulmonary angiogram (CTPA)CT imaging basics for StrokeCURB 65 scoreCabergolineCaecal VolvulusCaisson Disease - Decompression sicknessCalcitoninCalcitriol (1,25 Dihydroxycholecalciferol)Calcium Chloride or GluconateCalcium PhysiologyCalcium Pyrophosphate Deposition (Pseudogout)Calcium ResoniumCalcium channel blockers toxicityCalot's triangleCampylobacterCancer of Unknown PrimarCandesartanCandidiasisCannabis toxicityCapecitabineCapnocytophaga canimorsusCapnographyCapreomycinCaptopriCarbamazepineCarbapenemase-producing EnterobacteriaceaeCarbimazoleCarbon monoxide poisoningCarcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)Carcinoid Heart DiseaseCarcinoid Tumour SyndromeCarcinoma of the Bile DuctCarcinoma of the GallbladderCardiac Amyloid heart diseaseCardiac Anatomy and PhysiologyCardiac Catheter ablationCardiac InfectionsCardiac MRICardiac Resynchronisation Therapy (CRT) PacemakerCardiac Valve replacementCardioembolic strokeCardiogenic Pulmonary OedemaCardiogenic shockCardiology - History TakingCardiology Exam ListCardiology ExaminationCardiology Valves SummaryCardiopulmonary bypassCarmustineCarotid Artery anatomyCarotid Body TumourCarotid EndarterectomyCarotid Sinus SyncopeCarotid StentingCarotid artery DissectionCarotid sinus massageCarpal tunnel syndromeCarvedilolCase 01 Sudden weaknessCase 02 Loss of speechCase 03 Adult male weak legsCase 04 High calciumCase 05 High Potassium and heart failureCase 06 High calcium and weight lossCase 07 Weak eyesCase 08 Weak faceCase 09 A cause of DeliriumCase 10 Older patient presenting post strokeCase 11 Young patient with acute headacheCase 20 Young patient with acute headacheCase 21 HypoglycaemiaCase 22Case 23 Old man with tremorCase 24 Cancer and weakCase 99 (Acute breathlessness)Case TemplateCat Scratch DiseaseCataractCatheter Related Urinary Tract infection UTICatheter related Blood stream infectionCatheter related UTICauda equina syndromeCaudate NucleusCauses of Airway ObstructionCauses of Avascular Necrosis of Femoral headCauses of Sore throatCauses of WeaknessCavernous angiomas (Cavernomas)Cavernous sinusCavernous sinus thrombosisCefaclorCefalexinCefotaximeCeftazidimeCeftriaxoneCefuroximeCelecoxibCell Response to InjuryCellular Anatomy and PhysiologyCellulitisCentral Cord SyndromeCentral Retinal Vein Occlusion (CRVO)Central Retinal artery Occlusion (CRAO)Central Venous line InsertionCentral pontine myelinolysisCephalosporinsCerebellar Anatomy Physiology Signs DiseaseCerebellar HaemorrhageCerebellar StrokeCerebral Amyloid angiopathy (CAA)Cerebral AneurysmsCerebral AngiitisCerebral Atrophy vs HydrocephalusCerebral CortexCerebral MetastasesCerebral PalsyCerebral PerfusionCerebral Salt WastingCerebral Venous Sinus thrombosisCerebral arteritisCerebral microbleedsCervical Cancer screeningCervical Spine injuryCervical cancerCervical spondylosisCetirizineChancroidCharcot Foot Syndrome (CFS)Charcot Marie Tooth (CMT) diseaseChediak Higashi syndromeChest Abdomen anatomyChest X Ray #1Chest X Ray InterpretationChest drain InsertionChlamydia - Chlamydophila pneumoniaeChlamydia psittaciChlamydia trachomatisChlorambucilChloramphenicolChlordiazepoxideChloroquineChlorphenamine(Chlorpheniramine)ChlorpromazineCholangiocarcinomaCholera (Vibrio cholera)Cholestatic JaundiceCholesteatomaCholesterol - LipidsCholinergic crisis-syndromeChondrocalcinosisChorea - BallismusChoreoacanthocytosisChromosome instability syndromesChronic BronchitisChronic HepatitisChronic InflammationChronic Inflammatory Demyelinating polyneuropathyChronic Interstitial NephritisChronic Kidney Disease (CKD)Chronic Lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL)Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia (CML)Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)Chronic PancreatitisChronic PeritonitisChronic Radiation EnteritisChronic Urinary RetentionChronic Vision Uni-Bilateral loss (Blindness)Chronic and recurrent MeningitisChronic liver diseaseChronic mucocutaneous candidiasisChronic stable anginaChylomicronsCiclosporinCimetidineCinacalcetCiprofloxacinCirrhosisCisplatinCitalopramCladribineClarithromycinCleft lip or palateClindamycinClopidogrelClostridium botulinumClostridium difficileClostridium perfringensClostridium tetani - TetanusClotrimazole creamClotting pathwaysClozapineCo Careldopa (Sinemet)Co-Amoxiclav (Augmentin)Co-Beneldopa (Madopar)Co-codamolCo-trimoxazoleCoagulopathyCoal Worker's PneumoconiosisCoarctation of the Aorta (CoA aortopathy)Cocaine abuseCocaine induced chest painCocaine toxicityCoccidioidomycosisCodeineCoeliac diseaseCogan SyndromeColchicineCold Agglutinin Disease (CAD/AIHA)CollagenColloid cyst in the third ventricleColloidsColonic (Large bowel) ObstructionColonoscopyColorectal cancerColorectal polypsColposcopyComa managementCombined Oral contraceptive pill (COCP)Common Peroneal Nerve (CPN)Common variable immunodeficiencyComparing Rheumatoid and OsteoarthritisComplementComprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA)Confirming DeathCongenital Acyanotic Heart Disease (Children)Congenital Adrenal hyperplasiaCongenital Complete Heart BlockCongenital Cyanotic Heart Disease (Children)Congenital HypothyroidismCongenital Talipes Equinovarus - ClubfootConstipationConstrictive PericarditisContact allergic dermatitisContinuous Positive Airways Pressure (CPAP)Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysisContraceptionConus Medullaris syndromeCor PulmonaleCoronary artery bypass graft surgeryCoronavirus SARS-CoV-2 COVID 19Corticobasal degeneration (Dementia)Corticosteroid-related psychosisCorticosteroidsCorynebacterium diphtheriaeCotard delusionCoxiella BurnetiiCranial nerves and examinationCraniopharyngiomaCreatinine ClearanceCremation forms (UK)Creutzfeldt Jakob disease (Dementia)Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic feverCritical illness neuromuscular weaknessCrohn's diseaseCroupCryptococcus neoformans infectionsCryptogenic Fibrosing AlveolitisCryptogenic Organising Pneumonia (COP-BOOP)CryptosporidiosisCrysal arthritisCrystalloidsCushing diseaseCushing syndromeCutaneous LeishmaniasisCyanide toxicityCyanosis - Central and PeripheralCyclizineCyclo-oxygenase (COX) enzymesCyclophosphamideCycloserineCys leukotriene receptor antagonistsCystic FibrosisCystinosisCystinuriaCytokinesCytomegalovirus infectionsD DimerDNA and RNA short notesDNA replicationDabigatranDalteparinDandy Walker syndromeDantroleneDapagliflozinDarier's DiseaseDarunavirDeQuervain's thyroiditisDeath Certificates (UK)Deep brain stimulationDeep vein thrombosis (DVT)Dehydration PhysiologyDelayed Puberty CriteriaDemeclocyclineDementia with Lewy bodiesDementiasDemyelinating DiseasesDengue FeverDenosumab (Prolia)Dental AnatomyDentatorubral pallidoluysian atrophyDepressionDermatitis HerpetiformisDermatology termsDermatomesDermatomyositisDermoid cystsDesferrioxamineDesmopressin (DDAVP)Desogestrel (Progestogen Only Pill)Developmental Dislocation (Dysplasia) of the HipDevelopmental MilestonesDexamethasoneDiGeorge syndrome (thymic aplasia)Diabetes Insipidus (Cranial and Nephrogenic)Diabetes Mellitus Type 1Diabetes Mellitus Type 1 and DKA (children)Diabetes Mellitus Type 2Diabetes Mellitus in pregnancyDiabetes on the wardDiabetic Autonomic Neuropathy (DAN)Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) AdultsDiabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) with SGLT2 InhibitorsDiabetic NephropathyDiabetic RetinopathyDiabetic amyotrophyDiabetic footDiamond-Blackfan anaemiaDiamorphineDiaphragmatic disordersDiarrhoeaDiazepamDidanosine (ddI)DiethylstilbestrolDifferentials causes of Foot DropDifferentials of ABCDifferentials of Generalised lymphadenopathyDifferentials of Painful thighDifferentials of XXXDiffuse Oesophageal spasmDiffuse large B-cell lymphomaDiffusion CapacityDigoxinDigoxin ToxicityDihydrocodeineDilated cardiomyopathyDiltiazemDiphtheriaDipyridamoleDischarges against adviceDiscoid lupus erythematosus (DLE)Disease templateDiseases with associated cancersDislocation Sternoclaivcular jointDisopyramideDisseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC)Distributive ShockDisulfiram (Antabuse)DobutamineDog BitesDog Bites HandDominant R wave in V1DomperidoneDonepezil (Aricept)DonovanosisDopamine HydrochlorideDopamine agonistsDown's syndrome (Trisomy 21)DoxapramDoxazosin (Cardura)DoxepinDoxorubicin (Adriamycin)DoxycyclineDrivingDrowningDrug Induced Parkinson diseaseDrug Reaction Eosinophilia Systemic Symptoms DRESSDrug TemplateDrug Toxicity - clinical assessmentDrug Toxicity with Specific AntidotesDrug induced Lupus ErythematosusDrug induced liver diseaseDrugsDrugs ListDrugs to Avoid in Acute Renal failureDrugs to avoid ElderlyDrugs to avoid in Liver failureDry and Wet GangreneDual X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA)Duchenne muscular dystrophyDulaglutide GLP-1 agonistDuloxetineDuodenal Atresia (Children)Dupuytrens contractureDysenteryDysphagiaECG - Acute Coronary SyndromeECG - Acute ST Elevation Myocardial InfarctionECG - Atrial fibrillationECG - Atrial flutterECG - BasicsECG - Broad complex tachycardia (possible VT)ECG - Brugada syndromeECG - Causes of a Dominant R wave in V1ECG - Early Repolarisation vs STEMIECG - First degree AV BlockECG - Heart BlockECG - HyperkalaemiaECG - InterpretationECG - Ischaemic Heart DiseaseECG - Left Axis DeviationECG - Left Bundle Branch Block LBBBECG - Left Ventricular HypertrophyECG - Low Voltage ComplexesECG - Narrow complex tachycardiaECG - Normal appearanceECG - Pathological Q wavesECG - QT intervalECG - Right Axis DeviationECG - Right Bundle Branch Block RBBBECG - ST-T T waves changesECG - Supraventricular tachycardia ECG - The QRS complexECG - Tutorial from Queens UniversityECG - Ventricular fibrillationECG - Ventricular tachycardiaECG - Wolff Parkinson White syndrome (WPW)ECG - short PR intervalECG - sinus pauseECG - tall R wave V1ENT Exam - Assessing hearingENT infectionsEbola Virus DiseaseEbstein anomalyEchinocytesEchocardiogramEcstasy toxicityEctopia lentis (subluxation of the lens)Ectopic PregnancyEctropionEculizumabEdoxaban (Lixiana)Edward syndrome (trisomy 18 syndrome)Efavirenz (Sustiva) EFVEhlers-Danlos syndromesEhrlichiosisEikenella corrodensEisenmenger's syndrome (Children)Elbow fractures and InjuriesElectrical injuryEloquent brainEmergency DrugsEmphysemaEmpty sella syndromeEmtricitabine (Emtriva) FTCEnalaprilEnd of Life Care PrescribingEndocarditis and StrokeEndocrinology Lab valuesEndometrial (Uterine) CancerEndometriosisEndoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography XEndothelinsEnfuvirtideEnoxaparin Sodium (Clexane-Lovenox)EnoximoneEntacaponeEnterococciEnteropathic SpondyloarthritisEnzyme inducers and inhibitorsEosinophilic granulomatosis (Churg Strauss)EpendymomaEpidural HaematomaEpidural abscessEpilepsy - General ManagementEpilepsy - Idiopathic Generalised EpilepsyEpilepsy - Mesial temporal lobe epilepsyEpilepsy - Post TraumaticEpilepsy in PregnancyEpiscleritisEpistaxisEplerenoneEponymous brainstem strokesEpstein-Barr Virus infectionEquivalent doses of OpiatesErb PalsyErgocalciferol (Calciferol)Erlotinib (Tarceva)Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiaeErythema MultiformeErythema NodosumErythrocyte Sedimentation rate (ESR)ErythrocytesErythrodermic PsoriasisErythromycinEscherichia coliEscitalopramEsomeprazoleEssential Thrombocythaemia (ET)Essential TremorEtanerceptEthambutolEthanolEthanol toxicityEthylene glycol toxicityEtomidateEtravirine (intelence) ETREwing sarcomaExenatide (Byetta) GLP1 agonistExercise stress testExploding head syndromeExtradural haematomaExtrapyramidal symptomsExtrinsic Allergic alveolitis (Hypersensitivity)Eye infectionsEzetimibeFabry diseaseFacial NerveFacioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophyFactor V Leiden DeficiencyFaecal CalprotectinFahr syndromeFailure to thrive or Faltering growthFamilial Adenomatous polyposis (FAP)Familial AmyloidosisFamilial HypercholesterolaemiaFamilial Mediterranean Fever (FMF)Familial hypocalciuric hypercalcaemia (FHH)Family Tree (Pedigree)FamotidineFanconi AnaemiaFanconi SyndromeFat embolismFatigue - CausesFatty acidsFebrile seizuresFelodipine (Dihydropyridine)Femoral HerniaFemoral triangleFemur fractures and InuriesFentanyl - FentanilFerritinFerrous Fumarate - Gluconate - SulphateFetal Alcohol SyndromeFetal circulationFever - Pyrexia of unknown origin (FUO PUO)Fever in a travellerFibratesFibrinogenFibromuscular dysplasiaFibromyalgiaFidaxomicinFinasteride (5 alpha-reductase inhibitor)First SeizureFitz-Hugh Curtis SyndromeFlail ChestFlecainide AcetateFlexor sheath infection (flexor tenosynovitis)FlucloxacillinFluconazoleFlucytosineFludrocortisoneFluid balances statusFlumazenil (Annexate - Romazicon)FluoxetineFocal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis (FSGS)Foix-Alajouanine syndromeFolate (Folic) acidFolate deficiencyFolinic acid (Leucovorin)FomepizoleFondaparinuxFood borne diseaseFoscarnet SodiumFosfomycinFosphenytoinFoster Kennedy SyndromeFournier's gangreneFracture TemplateFractured ClavicleFractured Neck of FemurFractured Pubic RamusFractured ScapulaFractured Shaft FemurFractured Tibia and FibulaFractures Shaft HumerusFractures in ChildrenFractures of Upper humerusFragile X syndromeFrailtyFraser guidelines and Gillick CompetenceFree RadicalsFriedreich's AtaxiaFrontotemporal dementiaFull or Complete Blood Count (FBC CBC)FungiFurosemide (Frusemide)Fusidic acidFusobacteria - Tropical ulcerFusobacteriumG protein-coupled receptorsGP Emergency Drugs CarriedGabapentinGalactorrhoeaGalantamineGamete intra-fallopian tube transfer (GIFT)Gamma Glutamyl Transferase (GGT)Gamma hydroxy butyrate (GHB) toxicityGanciclovir - ValganciclovirGardner syndromeGardnerella vaginalisGas GangreneGastric (MALT) LymphomaGastric CancerGastric Outlet obstruction (pyloric stenosis)GastrinomaGastro Intestinal Stromal Tumours (GIST)Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux (Adult GORD)Gastro-Oesophgeal Reflux (Paediatrics GORD)GastroenteritisGastroenterology Exam ListsGastroenterology ExaminationGastroenterology HistoryGastroenterology assessment - JaundiceGastrointestinal anatomy and physiologyGastrointestinal perforationGastrostomy (PEG) tubesGaucher's diseaseGene componentsGenetic DiseasesGentamicinGiardiasisGilbert's syndromeGingival (Gum) hyperplasia-hypertrophyGitelman's syndromeGlasgow Blatchford ScoreGlasgow Coma scaleGlatiramer acetate (Copaxone)GlibenclamideGliclazideGlimepirideGlipizideGlobus PallidusGlomerulonephritisGlossitisGlucagonGlucagonomaGlucose 6 phosphate dehydrogenase deficiencyGlucose Tolerance TestGlutamateGlycated HaemoglobinGlyceryl Trinitrate (GTN)Glycogen storage diseasesGlycolysis_Krebs_Electron_Transport_ChainGlycopyrronium BromideGoitreGolfer's ElbowGolimumab (Simponi)Goodpasture's syndrome (Anti GBM disease)Goserelin (Zoladex)Gradenigo's syndromeGrades of RecommendationGram StainGranuloma annulareGranulomatosis with Polyangitis GPA (Wegener)Graves DiseaseGriseofulvinGrowth Hormone DeficiencyGuillain Barre SyndromeGum hypertrophyGuthrie test New Born blood spotGynaecological History TakingGynaecomastiaHAS-BLED scoreHIV and Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP)HIV and Pre-exposure prophylaxisHIV associated nephropathy (HIVAN)HIV disease AssessmentHTLV-1 Associated myelopathyHaematemesisHaematology Examination - SplenomegalyHaematology Lab valuesHaematuria Mild to SevereHaemodialysisHaemoglobinsHaemolysisHaemolytic AnaemiaHaemolytic Uraemic syndromeHaemolytic disease of the newbornHaemophilia AHaemophilia BHaemophilus aegyptiusHaemophilus ducreyiHaemophilus influenzaeHaemophilus parainfluenzaeHaemopoiesisHaemorrhagic TransformationHaemorrhagic strokeHaemorrhoids (Piles)Hairy Cell LeukaemiaHairy LeukoplakiaHallervorden-Spatz disease (PKAN)HaloperidolHamman-Rich syndromeHand foot and mouth diseaseHand fractures and InjuriesHantavirus infectionsHartmann's solution (Ringer's lactate)Hartnup disease*Hashimoto's (Steroid responsive) EncephalopathyHashimoto's thyroiditisHbA1cHead (Brain) InjuryHead and Neck CancersHeadache - Analgesic overuseHeadache - Assessing Acute and SevereHeadache - Basilar MigraineHeadache - ClusterHeadache - Low CSF pressureHeadache - MigraineHeadache - TensionHeadaches - GeneralHearing aidsHeat StrokeHelicobacter pyloriHelvetica Spotted feverHemicraniectomyHenoch-Schonlein purpuraHeparin - GeneralHeparin - Low Molecular Weight HeparinHeparin - Unfractionated HeparinHeparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT)Hepatic EncephalopathyHepatitis AHepatitis BHepatitis CHepatitis DHepatitis EHepatocellular CarcinomaHepatorenal syndromesHereditary ElliptocytosisHereditary HaemochromatosisHereditary Haemorrhagic TelangiectasiaHereditary Spastic ParaparesisHereditary SpherocytosisHereditary angio-oedemaHereditary neuropathy with pressure palsiesHereditary non polyposis coli (Lynch syndrome)Herpes GestationisHerpes SimplexHerpes Simplex Encephalitis (HSV)Herpes VirusesHerpes Zoster Ophthalmicus (HZO) ShinglesHerpes simplex keratitis (HSK)Heyde syndromeHiatus herniaHiccups (Singultus)High Dose Dexamethasone Suppression TestHip pain in childrenHirschsprung disease (congenital megacolon)Hirsuitism XXXHistonesHistoplasmosisHodgkin LymphomaHolt-Oram syndromeHolter monitor (tape) 24-72 hHomocystinuriaHookwormHorner's syndromeHospital acquired Pneumonia (NICE 139)Human albumin solution (HAS)Human prion diseasesHumeral fractures and injuriesHunter's syndrome (MPS-2)Huntington ChoreaHurler's syndrome (MPS-1)Hydatid disease (Echinococcus)Hydatidiform moleHydralazineHydrocortisoneHydrogen BondsHydrops fetalisHydroxocobalaminHydroxocobalamin - Cyanocobalamin (B12)HydroxychloroquineHydroxyurea-HydroxycarbamideHyoscine (Buscopan)Hyper IgM syndromeHyperbaric Oxygen therapyHypercalcaemiaHyperglycaemic Hyperosmolar State (HHS)Hyperinsulinaemic-euglycemic therapy (HIET)HyperkalaemiaHyperkalaemic and Hypokalaemic Periodic ParalysisHypermagnesaemiaHypernatraemiaHyperphosphataemia (High phosphate)HyperprolactinaemiaHypersensitivity reactionsHypertensionHypertension in PregnancyHypertriglyceridaemia (HTG)Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM - HOCM)Hyperventilation SyndromeHyperviscosity syndromeHypocalcaemiaHypoglycaemiaHypogonadism (Female)Hypogonadism (male)HypokalaemiaHypokalaemic Periodic ParalysisHypomagnesaemiaHyponatraemiaHypoparathyroidismHypophosphataemia (Low phosphate)Hypopituitarism (Pituitary Failure)HypospadiasHypothermiaHypothyroidismHypovolaemic or Haemorrhagic ShockIL-12 receptor deficiencyIV ImmunoglobulinIbandronic acid (Bisphosphonate)IbuprofenIcatibantIdiopathic Intracranial hypertensionIdiopathic Parkinson diseaseIdiopathic Pulmonary FibrosisIgA Nephropathy (Berger's disease)Images - Spot diagosesImatinib mesylateImipenem (Primaxin) with CilastinImmune Reconstitution SyndromeImmune(Idiopathic) Thrombocytopenic Purpura (ITP)Immunoglobulin G4-related disease (IgG4-RD)ImpetigoImplantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD)Impulse control disordersInclusion Body MyositisIncubation periodsIndapamideIndinavir (IND)Infection screening in Septic patientInfections and their Microbial causeInfectious MononucleosisInfective ConjunctivitisInfective EndocarditisInfertilityInfliximabInfluenzaInguinal HerniaInitial Trauma AssessmentInjury Severity Score (ISS)Insomnia - sleep issuesInsulinInsulinomaInterferon BetaIntermittent ClaudicationInternal CapsuleInternuclear OphthalmoplegiaInterpreting HaematinicsInterstitial KeratitisIntestinal obstruction (Children)Intra Aortic Balloon PumpIntraabdominal abscessIntracerebral Haemorrhage (ICH) ScoreIntracranial HypertensionXIntravenous Iron Replacement (Ferrous)Intraventricular haemorrhage (neonates)Intubation and Mechanical VentilationIntussusception (Adults)Intussusception (Children)Iodine deficiency GoitreIpratropium Bromide (Atrovent)IrbesartanIron SaltsIron deficiency AnaemiaIron toxicityIrritable bowel syndromeIschaemic ColitisIschaemic StrokeIschaemic heart diseaseIsoniazidIsoprenalineIsosorbide DinitrateIsosorbide mononitrateIsotretinoin (Accutane)Ispaghula Husk (Fybogel)IvabradineJansen DiseaseJanus kinase 2Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndromeJob Syndrome (Hyper IgE syndrome)Jugular Venous Pressure (JVP)Junctional TachycardiaJuvenile DermatomyositisJuvenile Idiopathic arthritis (Stills Disease)Juvenile Myoclonic epilepsy (JME)Kallmann's syndromeKaposi sarcoma (KS)Karnofsky performance status scaleKawasaki diseaseKennedy SyndromeKeratoconusKernicterusKetamineKetoconazoleKlebsiella pneumoniaKlinefelter Syndrome (Children)Klumpke palsyKnee fractures and InjuriesKoebner phenomenonKugelberg Welander syndromeKwashiorkorL-Thyroxine (T4)Labetalol (Trandate)Labyrinthitis - Vestibular NeuronitisLactateLactate dehydrogenase (LDH)Lactic acidosisLactobacillus acidophilusLactose IntoleranceLactuloseLady Windermere syndromeLambert-Eaton syndrome (LEMS)Lamivudine (3TC)LamotrigineLangerhans Cell Histiocytosis XLansoprazoleLanthanumLateral Medullary SyndromeLaxativesLe Fort FracturesLead toxicityLeber hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON)LeflunomideLegal definition of BlindnessLegionella pneumophilaLeishmaniasis (Cutaenous and Visceral)Lemierre's syndromeLenalidomide (Revlimid)Length Dependent PolyneuropathyLennox-Gastaut syndromeLenticulostriate branch occlusionLeprosyLeptinLeptospira interrogansLeptospirosis (Weil's Disease) (Notifiable)Leriche syndrome (aortoiliac occlusive disease)Lesch-Nyhan syndrome (Children)LeukaemiaLeukaemias in GeneralLeukoariosisLeukocytoclastic vasculitisLeukotrienesLevetiracetam (Keppra)LevodopaLevomepromazineLevosimendanLi Fraumeni syndromeLichen PlanusLiddle's syndromeLidocaine(Lignocaine)Lightning strikeLimb girdle dystrophyLimbic EncephalitisLinagliptin (Trajenta)LinezolidLinkageLiothyronine Sodium L-Triodothyronine (T3)Lipid emulsion therapy - IntralipidLipid management [NICE 2014]LipoatrophyLipoprotein lipase deficiencyLiraglutide (Victoza)LisinoprilListerial MeningitisListeriosisLithiumLithium toxicityLivedo ReticularisLiver Anatomy PhysiologyLiver BiopsyLiver Function TestsLiver TransplantationLiver abscessLiver disease in PregnancyLocalisation of cortical functionLofepramineLong QT syndrome (LQTS) AcquiredLong QT syndrome (LQTS) CongenitalLong term Oxygen therapy (LTOT)Loop diureticsLooser's zonesLoperamideLopinavirLoratadineLorazepamLosartanLow Dose Dexamethasone Suppression TestLower Gastrointestinal BleedingLugol iodineLumbar puncture and CSF interpretationLumbrosacral radiculopathyLung AbscessLung CancerLung ComplianceLung EmpyemaLung TransplantLupus NephritisLupus VulgarisLyme diseaseLymphocytic HypophysitisLymphogranuloma Venereum (LGV)LyonizationLysosomal storage diseasesMCune Albright syndromeMELASMacrocytic anaemiaMacroglossiaMagnesium PhysiologyMagnesium Sulphate - SulfateMagnetic resonance cholangiopancreatographyMagnetic resonance imagingMajor Histocompatibility complexMalabsorption - small intestineMalaria (non falciparum)Malaria FalciparumMale InfertilityMale Urethral CatheterisationMale erectile dysfunctionMalignant AscitesMalignant Hyperpyrexia (Malignant Hyperthermia)Malignant HypertensionMalignant MelanomaMalignant pleural mesotheliomaMallet FingerMallory-Weiss TearMalnutrition Universal Screening ToolManiaMannitolMantle cell lymphomaMarantic EndocarditisMarasmusMaraviroc (Celsentri)Marfan syndromeMarginal Zone LymphomaMassive HaemoptysisMaturity Onset Diabetes of the Young (MODY)McArdles disease (type V)Measles (notifiable)MebeverineMeckel's diverticulumMeconiumMedian NerveMedical Mnemonics Basic SciencesMedical Mnemonics CardiologyMedical Mnemonics EndocrineMedical Mnemonics Mental HealthMedical Mnemonics MiscellaneousMedical Mnemonics NeurologyMedical ProceduresMedical TeethMedullary Sponge kidneyMedulloblastomaMefenamic acidMefloquine (Larium)Megaloblastic anaemiaMelatoninMelioidosisMemantine HydrochlorideMembranous GlomerulonephritisMenetrier diseaseMeniere diseaseMeningiomaMeningitis in the ImmunocompromisedMenopauseMenstrual cycleMental Capacity Act 2005Mental Health Act 1983Mental State ExaminationMercaptopurineMeropenemMesalazine (Aminosalicylate)Mesangiocapillary GlomerulonephritisMesenteric infarctionMetabolic Syndrome XMetabolic acidosisMetabolic alkalosisMetachromic leucodystrophyMetastatic AdenocarcinomaMetastatic bone diseaseMetforminMethaemoglobinaemiaMethanol ToxicityMethodoneMethods to reduce toxin absorptionMethotrexateMethylcelluloseMethylprednisoloneMetoclopramideMetolazoneMetoprololMetronidazole (Flagyl)Metyrapone (Metopirone)MiconazoleMicroangiopathic Haemolytic anaemiaMicrocytic anaemiaMicroscopic PolyangiitisMicroscopic colitisMicrostomiaMidazolamMiddle East Resp Syndrome (MERS) CoronavirusMidodrineMigraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS)Miller-Fisher syndromeMilwaukee shoulder syndromeMini Mental State Examination (MMSE)Minimal Change Disease GlomerulonephritisMinocyclineMinoxidilMirabegronMirizzi syndromeMirtazapineMiscarriageMisoprostolMitochondrial diseasesMitral Regurgitation (Incompetence)Mitral StenosisMitral Stenosis vs Regurgitation - DominanceMitral Valve prolapseMittleschmerzMixed Connective Tissue Disease (MCTD)Mobility aidsModified Duke Criteria for EndocarditisModified Oxford Handicap Scale (MOHS)Modified Rankin ScoreMolluscum contagiosumMonoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significanceMonocular loss of visionMonocytesMonosodium glutamate (MSG) syndromeMontelukastMontreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA)Moraxella catarrhalisMorphine SulphateMosquito borne diseasesMotor Neuron Disease (MND-ALS)Moyamoya diseaseMucormycosisMultifocal Atrial TachycardiaMultifocal Motor Neuropathy with Conduction blockMultiple Antithrombotics AnticoagulantsMultiple Endocrine Neoplasia type 1 (MEN1)Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia type II (MEN2)Multiple MyelomaMultiple PregnancyMultiple Sclerosis (MS) DemyelinationMultiple System Atrophy (MSA)Mumps (Notifiable)Muscles of the Abdominal RegionMuscles of the BackMuscles of the Head and NeckMuscles of the Lower LimbMuscles of the Pelvis and PerineumMuscles of the Thoracic RegionMuscles of the Upper limbMyasthenia GravisMycobacterium TuberculosisMycophenolate mofetilMycoplasma pneumoniaeMycoplasmasMycosis Fungoides (Sezary Syndrome)Myelodysplastic syndrome (Myelodysplasia)MyelofibrosisMyelofibrosis vs CMLMyelopathyMyeloproliferative disordersMyobacterium avium Complex InfectionMyocardial perfusionMyoclonusMyotonic dystrophy - Dystropica myotonicaMyxoedema comaN-Acetylcysteine (Parvolex)NEWS Reacting to Low Oxygen SaturationsNICE Guidelines LinksNICE Trauma Guidance Summary 2016NSAID toxicityNaloxone (Narcan) Opiate antagonistNaproxenNarcolepsyNasal polypsNasogastric tube insertionNatalizumab (Tysabri)National Early Warning Score NEWS 2 ScoreNeck PainNeck swellings and lumpsNecrotising Enterocolitis (Infants)Necrotising fasciitisNeedlestick injuryNefopamNeisseria gonorrhoeaeNeisseria meningitidisNelson SyndromeNeomycinNeonatal Abstinence Syndrome NASNeonatal JaundiceNeonatal Lupus ErythematosusNeonatal meningitisNeostigmineNephritic syndromeNephroblastoma (Wilm's tumour)Nephrotic syndromeNephrotoxic drugsNerve conduction studiesNerve fibresNeuroanatomy 101Neuroanatomy imagesNeuroblastomaNeurocysticercosisNeuroferrinopathyNeurofibromatosis Type 1Neurofibromatosis Type 2Neuroleptic Malignant SyndromeNeurological - Relative Afferent pupillary defectNeurological - Vision and Eye movementsNeurological Examination - CognitionNeurological Examination - Cortical FunctionsNeurological Examination - MotorNeurological Examination - SensoryNeurological Examination - Speech&LanguageNeurological ListsNeurological assessment - PtosisNeurological examination - EyesNeurological or ENT Examination - NystagmusNeurology - History takingNeurology Exam - Reflex findingsNeuromyelitis optica*Neuropathic Pain ManagementNeurotransmittersNeutropeniaNeutropenic SepsisNeutrophil Alkaline PhosphataseNeutrophilsNevirapine (Viramune) NEV-NVPNiacin deficiency (Pellagra Vitamin B6)Nicardipine (Cardene)NicorandilNiemann-Pick diseaseNifedipineNimodipine (Nimotop)Nitric OxideNitrofurantoinNitrous oxideNizatidineNocardiaNoise induced hearing lossNon Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease NAFLDNon Convulsive Status EpilepticusNon Hodgkin LymphomaNon alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)Non gonococcal urethritisNon invasive ventilation (NIV)Non steroidal anti inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)Non sustained Ventricular tachycardiaNoonan syndromeNoradrenalineNormal DistributionNormal Pressure HydrocephalusNormal Saline 0.9%Normocytic anaemiaNortriptylineNosocomial infectionsNotifiable disease and organisms UKNutrition in Infants BreatsfeedingNystatinOSCE - Administer IV InjectionOSCE - Blood cultureOSCE - VenepunctureOSCE - Venous Cannula InsertionObsessive-Compulsive disorderObstetric definitionsObstructive ShockObstructive Sleep ApnoeaOctreotideOculomotor Nerve (IIIrd Cranial Nerve)OedemaOesophageal CarcinomaOesophageal Perforation - RuptureOesophageal Variceal BleedingOesophagogastroduodenoscopyOlanzapineOlfactory Nerve (I)OligodendrogliomaOlmersartanOlsalazine (Aminosalicylate)OmalizumabOmeprazoleOnchocerciasisOncogenic virusesOncological emergenciesOndansetronOne Table TemplateOphthalmology Exam ListsOpiate ToxicityOpiatesOpicaponeOpioid toxicityOptic Neuritis-NeuropathyOptic atrophyOptic tract anatomyOral Aphthous UlcersOral CandidiasisOral LeukoplakiaOrbital vs Preorbital CellulitisOrganism and sensitivitiesOrganophosphate (OP) PoisoningOrphenadrineOrthopaedic infectionsOrthostatic - Postural hypotensionOscillopsiaOseltamivir - TamifluOsteoarthritisOsteogenesis ImperfectaOsteogenic sarcoma (Osteosarcoma)Osteomalacia-Rickets-Vitamin DOsteomyelitisOsteonecrosis of the jawOsteopetrosisOsteoporosisOtitis Externa (Malignant)Otitis MediaOtosclerosisOttawa rules for ankle and foot x-rayOvarian CancerOvarian CystOvaryOxford community stroke project (Bamford)Oxybutynin (Ditropan)Oxycodone (Oxycontin-Oxynorm)Oxygen delivery devicesOxytetracyclinePEDIS Score for Diabetic Foot UlcersPOEMS syndromePabrinexPacemaker DDDPacemaker VVIPacemaker syndromePacemakersPacing - Indications for temporary pacingPaediatric emergenciesPaediatricsPaget's (Bone) diseasePain ManagementPainful Shoulder syndromesPalliatiion - Nausea Dyspnoea Secretions PainPalliation prescribingPalpitationsPamidronate (Bisphosphonate)Pancoast tumour (Cancer)Pancreatic CancerPanton-Valentine leucocidin toxinPantoprazolePapilloedemaParacetamol (Acetaminophen)Paracetamol toxicityParadoxical embolisationParaneoplastic Encephalitis with NMDA antibodiesParaneoplastic Limbic Encephalitis (Dementia)Paraneoplastic cerebellar degenerationParaphimosisParaquat toxicityParkinson Plus syndromesParkinsonismParonychiaParoxetineParoxysmal Nocturnal HaemoglobinuriaParvovirus (Erythrovirus 19) B19 infectionPasteurella multocidaPatau syndrome (trisomy 13)Patent Ductus arteriosus (PDA) (Children)Patent Foramen Ovale (PFO)Pathogen - pattern recognition receptorsPathological bone fracturePegvisomantPelvic fracturesPemphigus VulgarisPenetrating Abdominal TraumaPenetrating Thoracic TraumaPenicillaminePenicillinsPenile CancerPeptic ulcer diseasePercutaenous Coronary Intervention (PCI ACS)PergolidePericardial Effusion_TamponadePerimesencephalic Subarachnoid haemorrhagePerindoprilPerinephric abscessPerioperative AnticoagulationPeripartum cardiomyopathyPeripheral Arterial Disease (PAD)Peripheral Cannula InsertionPeripheral Nerve Palsies*Peripheral neuropathyPeripherally inserted central cathetersPernicious anaemiaPerthes disease (Osteochondritis of the Hip)PethidinePeutz-Jeghers syndromePhaeochromocytomaPhagocytesPharmacokinetic notesPharmacokineticsPharyngeal arch derivativesPhenobarbital sodiumPhenoxymethylpenicillin (Penicillin V)PhentolaminePhenylketonuria (PKU)Phenytoin (Dilantin)Philadelphia chromosomePhimosisPhobic disordersPhocomelia and ThalidomidePhosphorusPhysiology of visionPicolax - CitrafleetPilonidal Abscess (sinus)Pioglitazone (Thiazolidinediones)Pituitary AdenomaPituitary Anatomy and PhysiologyPituitary ApoplexyPityriasis or Tinea versicolor infectionsPityriasis roseaPivmecillinam (a penicillin antibiotic)Placenta praeviaPlacental abruptionPlantar fasciitisPlasmacytomaPlasmapharesisPlasmidsPleural effusionPleural tap (thoracentesis)Pneumococcal meningititisPneumoconiosisPneumocystis jirovecii pneumoniaPneumoniaPneumothoraxPoisons eliminated Haemodialysis - perfusionPoliomyelitisPolyarteritis nodosa (PAN)Polyarticular arthritisPolycystic Ovary syndromePolycythaemia Vera (primary polycythaemia)Polymerase chain reactionPolymorphic light eruptionPolymyalgia RheumaticaPolymyositisPolypharmacy Start CriteriaPolypharmacy Stop CriteriaPolyuriaPontine-Midbrain haemorrhagePorphyria Cutanea Tarda (PCT)Porphyria TestingPortal HypertensionPositron Emission TomographyPost Menopausal BleedingPost Operative ManagementPost Partum ThyroiditisPost Polio SyndromePost SplenectomyPost Streptococcal/Infectious GlomerulonephritisPost Stroke Epilepsy (PSE)Post traumatic stress disorderPost-exposure prophylaxis with ImmunoglobulinsPosterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome (PRESPosterior circulationPostpartum haemorrhagePotassium PhysiologyPralidoximePramipexole (Mirapexin)PrasugrelPravastatinPraxbind - IdarucizumabPraziquantelPrazosinPre-Operative AssessmentPreEclampsia, Eclapsmia and HELLPPrednisolonePrednisonePregabalinPremature LabourPremature MenopausePresbyacusisPrescribing InformationPrescribing in PregnancyPressure soresPrevotella (Bacteroides) melaninogenicaPriapismPrimaquinePrimary (Chronic simple) Open angle GlaucomaPrimary Biliary CirrhosisPrimary CNS LymphomaPrimary HyperparathyroidismPrimary Sclerosing CholangitisPrimary ciliary dyskinesiaPrimary hyperaldosteronism (Conn's syndrome)Primary progressive aphasia (Dementia)ProbenicidProchlorperazine (Stemetil)ProcyclidineProgressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy (PML)Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP)ProlactinomaPropafenonePropanthelinePropionibacteriumPropofolPropranololPropylthiouracilProstate cancerProsthetic ValvesProtamine SulfateProtein C DeficiencyProtein S DeficiencyProtein losing enteropathyProtein p53Protein synthesisProteusProthrombin 20210A mutationProthrombin Complex Concentrates (PCC)Prothrombin time and CoagulationProthrombotic disordersProton Pump InhibitorsProximal myopathyPrucalopridePsammoma bodiesPseudohypoparathyroidismPseudomonas infection (Pseudomonas aeruginosa)Psoas AbscessPsoriasisPsoriatic arthritisPsychogenic PolydipsiaPubic Lice (Pediculosis Pubis)Pulmonary Alveolar ProteinosisPulmonary Arteriovenous malformationPulmonary EmbolismPulmonary Eosinophilia and CXR changesPulmonary HypertensionPulmonary Hypertension - PrimaryPulmonary RegurgitationPulmonary StenosisPulmonary hypertension - SecondaryPulse oximetryPutamenPutaminal HaemorrhagePyloric stenosis (Children)Pyoderma gangrenosumPyonephrosisPyrazinamidePyridostigminePyruvate Kinase deficiencyQuetiapineQuinineQuinine toxicityRabiesRadial PulseRadial nerveRadiation exposureRadioactive iodine (I 131)Radiofrequency Catheter AblationRadius and Ulna fractures and InjuriesRaloxifeneRaltegravirRamiprilRamsay Hunt syndromeRanitidineRanolazineRapid sequence intubation (RSI)Rapidly Progressive GlomerulonephritisRasagilineRasburicaseRaynaud's PhenomenonReactive arthritisRectal ProlapseRed cell aplasiaRed eyeRefeeding syndromeReferring to Level 2 or 3 care (ITU ICU HDU)Refractive ErrorsRefsum's diseaseRelapsing polychondritisRemdesvir (Veklury)Renal Artery StenosisRenal Papillary NecrosisRenal Physiology IRenal Stones (Nephrolithiasis)Renal TransplantationRenal Tubular AcidosisRenal Vein ThrombosisRenal cell carcinomaRenal physiologyRenin and Aldosterone Renin ratio (ARR)Renin-angiotensin systemRespiratory (Chest) infections and pneumoniaRespiratory - History TakingRespiratory AcidosisRespiratory AlkalosisRespiratory Anatomy and PhysiologyRespiratory Disease InvestigationsRespiratory Distress Syndrome (Neonates)Respiratory ExaminationRespiratory Examination - Finger ClubbingRespiratory Failure (hypoxia-hypercarbia)Resting membrane potentialRestless legs syndromeRestriction enzymesRestrictive CardiomyopathyResuscitation - Adult Bradycardia AlgorithmResuscitation - Adult Tachycardia AlgorithmResuscitation - Advanced Life SupportResuscitation - Basic Life Support ABCDEResuscitation - Choking AlgorithmResuscitation - Post Resuscitation AlgorithmReteplaseReticulocytesRetinal detachmentRetinitis pigmentosaRetinoblastomaRetinoidsRetroperitoneal fibrosisRett SyndromeReversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndromeReye syndromeRhesus haemolytic diseaseRheumatoid arthritisRheumatology AutoantibodiesRheumatology Lab valuesRhodococcus equiRibavirinRicin ToxicityRickettsia (General Principles)Rickettsia africae (Tick Bite Fever)Rickettsia akariRickettsia conorii (Tick Bite Fever)Rickettsia prowazekiiRickettsia rickettsiiRickettsia tsutsugamushiRickettsia typhiRifampicin (Rifabutin Rifampin)RifaximinRilipivirine (Edurant) RVPRiluzole (Rilutek)Risedronate (Bisphosphonate)RisperidoneRitonavir (Norvir) RTVRituximab (Mabthera)Rivaroxaban (Xarelto)Rivastigmine (Exelon)Rocky Mountain Spotted FeverRocuroniumRotigotineRubella (German Measles) NotifiableSCL70 AntibodySMASH U Intracerebral Haemorrhage ClassificationSOCRATES mnemonicST segment changesSacubitril with ValsartanSalivary Gland DiseaseSalivary glandsSalmonella entericaSalmonella typhiSaquinivir (Invirase) SQVSarcoidosisSaxagliptin (Onglyza)ScabiesScarlet Fever (Scarlatina)SchistosomiasisSchizophreniaSchmidt's syndromeSciaticaSeborrheic DermatitisSecondary Brain TumoursSecondary MessengersSecondary dysmenorrhoeaSecondary hyperparathyroidismSedation and Analgesia on ITUSelective IgA deficiencySelective Serotonin reuptake Inhibitor toxicitySelective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI)SelegilineSelenium deficiencySennaSeptic Shock and Sepsis 3Septic arthritisSepticaemiaSeronegative SpondyloarthropathiesSerotonin syndromeSerratiaSevelamerSevere combined immunodeficiency disordersSex Linked RecessiveSheehan's syndromeShigella characteristicsShigellosis (Bacillary Dysentery)Shock (General Assessment)Short Synacthen test (SST)Short and Tall stature Growth in ChildrenShoulder dislocationsSick Euthyroid SyndromeSickle Cell DiseaseSideroblastic AnaemiaSigmoid VolvulusSildenafil (Viagra)SilicosisSilver Trauma - Age over 65SimvastatinSinus BradycardiaSinus Node diseaseSinus TachycardiaSitagliptinSitosterolemiaSjogren's syndromeSkin and soft tissue infectionsSkull AnatomySleep physiologySlipped Upper Femoral Epiphysis (SUFE)Small Bowel IschaemiaSmall Bowel ObstructionSmall vessel diseaseSmallpoxSmokingSnake BitesSneddon SyndromeSodium BicarbonateSodium NitroprussideSodium PhysiologySodium PicosulfateSodium Thiopental - Sodium ThiopentoneSodium Valproate (Epilim Depakote)Sodium Zirconium Cyclosilicate (Lokelma)Soft tissue injuries (sprains, strains)SolifenacinSolitary Pulmonary NoduleSotalol HydrochlorideSpetzler-Martin Grading of AVMSpina BifidaSpinal Cord AnatomySpinal Cord Arteriovenous MalformationsSpinal Cord CompressionSpinal Cord HaematomaSpinal Cord InfarctionSpinal StenosisSpirometrySpironolactoneSpleenSplenic RuptureSpondylolisthesisSpontaneous Bacterial PeritonitisSpontaneous intracranial hypotensionSquamous Cell CarcinomaSt John's WortStaphylococcal InfectionsStaphylococcus aureusStaphylococcus epidermidisStaphylococcus saprophyticusStatinStatus Epilepticus (Epilepsy)Stavudine (Zerit) d4TStevens-Johnson SyndromeStiff Person SyndromeStrabismus (Lazy Eye)Streptobacillus moniliformisStreptococci - anaerobesStreptococcusStreptococcus agalactiaeStreptococcus milleriStreptococcus pneumoniae (Pneumococcus)Streptococcus pyogenesStreptococcus viridansStreptokinaseStreptomycinStridorStroke - Arterial Occlusion and clinical correlateStroke - Epidemiology and risk factorsStroke - General ManagementStroke - ImagingStroke ASPECTS scoringStroke CollateralsStroke Risk FactorsStroke ThrombolysisStrongyloides stercoralis (threadworm)StrontiumSubacute Sclerosing PanencephalitisSubacute ThyroiditisSubarachnoid HaemorrhageSubclavian Steal SyndromeSubclavian vein thrombosisSubdural haematomaSucralfateSudden Cardiac Death (SCD)Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS)Sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL)SuicideSulfasalazine - SulphasalazineSulphonamide (Sulphamethoxazole)SumatriptanSuperior Mesenteric Artery (SMA) SyndromeSuperior Sagittal Sinus ThrombosisSuperior vena caval obstruction syndromeSupracondylar Femur FracturesSupracondylar Humerus FracturesSupraspinatus tendonitisSupraventricular TachycardiaSurgical CricothyroidotomySurgical prophylaxisSurgical site infectionSusac syndromeSuxamethoniumSydenham's choreaSynchronised DC CardioversionSyncopeSyndrome X (Cardiology)Syndrome of Inappropriate ADH (SIADH) secretionSyndromes with Severe Cognitive IssuesSyphilisSyringobulbiaSyringomyeliaSystemic AmyloidosisSystemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE)Systemic MastocytosisSystemic SclerosisT cellsTIMI scoreTMN Staging tumoursTNF receptor-associated periodic syndromeTORCH infectionsTURP Hyponatraemia syndromeTabes dorsalisTacrolimusTafamidisTakayasu arteritis (pulseless disease)Takotsubo CardiomyopathyTamoxifenTamsulosin (Flomax)Tanner Stages of Pubertal DevelopmentTardive DyskinesiasTay-Sachs diseaseTazocin (Tazobactam - Piperacillin)TeicoplaninTelomeresTemazepamTemozolomide (Temodal)Template XTemplate two columns listTemporal (Giant Cell GCA) ArteritisTenecteplaseTennis ElbowTensilon testTension PneumothoraxTerbutalineTeriparatideTerlipressinTertiary hyperparathyroidismTesticular CancerTesticular torsionTestingTetrabenazineTetracosactide (Synacthen)TetracyclinesTetralogy of Fallot (Children)Thalamic HaemorrhageThalamic Pain SyndromeThalamic Stroke SyndromeThalidomideTheophyllineTheophylline toxicityThiamineThird Degree (complete) Heart BlockThoracic TraumaThoracic anatomyThoracic outlet syndromeThrombocytosisThrombolysisThrombophilia testingThrombotic Thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP)Thyroglossal Cyst (Children)Thyroid CancerThyroid Function Tests and antbodiesThyroid GlandThyroid Storm - Thyrotoxic crisisThyroid Surgery (Thyroidectomy)Thyroid noduleThyrotoxicosis and HyperthyroidismTiagabineTibia and Fibula fractures and InjuriesTicagrelorTick ParalysisTimololTinea capitisTinidazoleTinzaparin (Innohep)Tiotropium (Spiriva)Titre - TiterTocilizumabTolbutamideTolcaponeTolosa Hunt SyndromeTolterodineTolvaptanTongue tie - ankyloglossia (Children)Topiramate (Topamax)Torsades de pointes (Polymorphic VT)Total Anomalous Pulmonary Venous DrainageToxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN)Toxic MegacolonToxic Shock SyndromeToxoplasmosisTramadolTranexamic AcidTranscatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI)Transfer factor (TLCO)Transfusion ten commandmentsTransient Global Amnesia (TGA)Transient Ischaemic Attack (TIA)Transient Monocular Blindness (TMB)Transoesophageal Echocardiography (TOE-TEE)Transplant and organ rejectionTransposition of the great arteries (Children)Transverse myelitisTrastuzumab (Herceptin)Traumatic Spinal InjuryTravellers DiarrhoeaTrazodoneTreponemaTriangles of the neckTrichinellosisTricuspid Atresia (Children)Tricuspid RegurgitationTricuspid StenosisTricyclic Antidepressant ToxicityTricyclic antidepressantsTrigeminal NerveTrigeminal neuralgiaTrihexyphenidyl (benzhexol)TrimethoprimTrinucleotide (triplet) repeatsTrochlear NerveTropheryma whipplei (Whipple disease)Tropical SprueTruncus Arteriosus (Children)TuberculosisTuberculous MeningitisTuberous sclerosisTularaemiaTumour Lysis SyndromeTumour markersTurcot's syndrome (Brain tumor polyposis syndrome)Turner's syndrome (Children)Two list Table templateTyphoid - Paratyphoid fever (Enteric Fever)Tyrosine Kinase receptorsUS vs UK Drug namesUbiquitinUlcerative ColitisUlnar nerveUltrasound - Echo basicsUndifferentiated Inflammatory Arthritis (Children)Unexplained symptomsUpper Gastrointestinal Bleed (GI Bleed)Upper-Lower Motor Neurone signsUrea and ElectrolytesUrethral syndomeUrinary CatheterisationUrinary Incontinence (Stress and Urge)Urinary Tract Infection (UTI Children)Urinary Tract InfectionsUrinary Tract ObstructionUrinary UTI Antibiotic guidanceUrine AnalysisUrothelial tumoursUrticariaUterusVIPomasVTE DVT PE in PregnancyVaginal CarcinomaValaciclovirValsartanVancomycinVariable rate intravenous insulin infusion VRIIIVariant (Prinzmetal) AnginaVaricella-Zoster (Chickenpox Shingles) InfectionVariegate PorphyriaVascular DementiaVasculitis - General Issues and ClassificationVasopressin (AVP) Antidiuretic hormoneVasovagal syncopeVaughan-Williams ClassificationVecuroniumVedolizumab (Entyvio)VenlafaxineVenous Insufficiency and Leg UlcersVenous access Venflons and Central linesVentilator associated pneumonia (VAP)Ventricular FibrillationVentricular Septal defect (VSD) (Children)Ventricular TachycardiaVentricular ectopic beatsVerapamilVertebral artery dissectionVertigoVesicoureteric reflux (VUR) (Children)Vibrio parahaemolyticusVibrio vulnificusVibrio vulnificus Vigabatrin (Sabril)VinblastineVincristineViral MeningitisViral associated cancersVirusesVisual acuityVitamin A deficiency (Children)Vitamin B1 Thiamine deficiencyVitamin B12 deficiencyVitamin B12 excessVitamin C deficiency (Scurvy)Vitamin D (1,25 OH2)Vitamin D (25 OH D)Vitamin D deficiencyVitamin D resistant rickets (Children)Vitamin K (Phytomenadione)Vitamin K deficiencyVitiligoVoltarol (Diclofenac)Von Gierke Disease (Children)Von Hippel LindauVon Willebrand DiseaseWaardenburg's syndrome (Children)Wagner Classification Diabetic foot ulcersWaldenstrom Macroglobulinaemia (WM)Wallerian DegenerationWarfarinWarfarin and BleedingWater PhysiologyWatershed InfarctsWerdnig Hoffman Disease (Children)Wernicke Korsakoff SyndromeWhite Blood Cells - LeukocytesWilliams Syndrome (Children)Wilson diseaseWiskott-Aldrich syndrome (Children)Wolff-Parkinson White syndrome (WPW)Wolfram syndrome (DIDMOAD)Wound healingX linked Agammaglobulinaemia (Bruton)X linked Hypophosphataemic ricketsX-linked IchthyosisX-linked lymphoproliferative disease (Children)Xeroderma pigmentosumYellow FeverYellow Nail SyndromeYersinia enterocoliticaYersinia pestis - Bubonic PlagueYersinia pseudotuberculosisZZAAAZZ_Abnormal charZabramski Classification of CavernomasZidovudine (Retrovir) AZT - ZDVZieve's syndromeZika virusZinc deficiencyZoledronic acidZollinger Ellison syndromeZolpidemZopicloneeGFR

Makindo Medical Notes.com |

|

|---|---|

| Download all this content in the Apps now Android App and Apple iPhone/Pad App | |

| MEDICAL DISCLAIMER:The contents are under continuing development and improvements and despite all efforts may contain errors of omission or fact. This is not to be used for the assessment, diagnosis or management of patients. It should not be regarded as medical advice by healthcare workers or laypeople. It is for educational purposes only. Please adhere to your local protocols. Use the BNF for drug information. If you are unwell please seek urgent healthcare advice. If you do not accept this then please do not use the website. Makindo Ltd | |

Spontaneous Pneumothorax

-

| About | Anaesthetics and Critical Care | Anatomy | Biochemistry | Cardiology | Clinical Cases | CompSci | Crib | Dermatology | Differentials | Drugs | ENT | Electrocardiogram | Embryology | Emergency Medicine | Endocrinology | Ethics | Foundation Doctors | Gastroenterology | General Information | General Practice | Genetics | Geriatric Medicine | Guidelines | Haematology | Hepatology | Immunology | Infectious Diseases | Infographic | Investigations | Lists | Microbiology | Miscellaneous | Nephrology | Neuroanatomy | Neurology | Nutrition | OSCE | Obstetrics Gynaecology | Oncology | Ophthalmology | Oral Medicine and Dentistry | Paediatrics | Palliative | Pathology | Pharmacology | Physiology | Procedures | Psychiatry | Radiology | Respiratory | Resuscitation | Rheumatology | Statistics and Research | Stroke | Surgery | Toxicology | Trauma and Orthopaedics | Twitter | Urology

Related Subjects: Asthma |Acute Severe Asthma |Exacerbation of COPD |Pulmonary Embolism |Cardiogenic Pulmonary Oedema |Pneumothorax |Tension Pneumothorax |Respiratory (Chest) infections Pneumonia |Fat embolism |Hyperventilation Syndrome |ARDS |Respiratory Failure |Diabetic Ketoacidosis

Treatment depends critically on whether it is a primary or secondary pneumothorax. Underlying lung disease means it is secondary and it is treated far more cautiously. Suspect a pneumothorax in any mechanically ventilated patient whose respiratory function deteriorates. It may only be detected by an increase in resistance to ventilation

About

- Spontaneous presence of air in the pleural space.

- Aged over 50 or with lung disease are classed as secondary and need admitted

Mechanism

- Penetrating from a hole in the visceral pleura into the lung

- Penetrating wound from oesophagus, mediastinum, diaphragm and associated structures

- Gas forming bacteria within an empyema

Types

- Primary - defined as age less than 50y, no significant smoking history, and no evidence of underlying lung disease

- Secondary - due to known lung disease

- Traumatic (consider under Trauma)

Classification

- Primary Pneumothorax

- Tall thin males aged 20-40 seem to be more at risk and commoner on right.

- Commoner in smokers possibly have subclinical lung disease

- Increased stresses on the lung apices in tall people cause a predisposition to subpleural bleb formation which can later cause a pneumothorax

- Risk of recurrence is 40% within 2 years especially tall who smoke

- Secondary Pneumothorax

- Trauma - especially penetrating chest trauma

- Iatrogenic trauma - pleural biopsy, lung biopsy, central line insertion

- High positive end-expiratory pressure ventilation

- Asthma, Cystic fibrosis, Emphysema

- Lung abscess, PCP pneumonia

- Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, Sarcoidosis

- Endometriosis/Catamenial pneumothorax - occurs within 72 hours of menses

- Oesophageal rupture

- Lymphangioleiomyomatosis, Lung carcinoma

- Histiocytosis X, Eosinophilic granuloma

- Marfan's syndrome, Homocystinuria

- Iatrogenic Pneumothorax

- Attempted internal jugular/subclavian vein access

- Pleural aspiration/biopsy

- Percutaneous lung/liver biopsy

- Transbronchial biopsy

- Intermittent positive pressure ventilation

Clinical

- May be asymptomatic

- Breathless - may be mild in small PTX

- Tachycardia, hypotension, cyanosis when severe or tension

- Localised chest pain and even a click or added sounds

- Affected side is hyper resonant with decreased breath sounds

- Tension pneumothorax the trachea is pushed away

Investigations

- PA CXR shows an absence of lung markings between the ribs and a line demarcating the edge of the lung. Expiratory films are no longer advocated. Lateral CXR may help if PTX is suspected and the PA chest is not definitive.

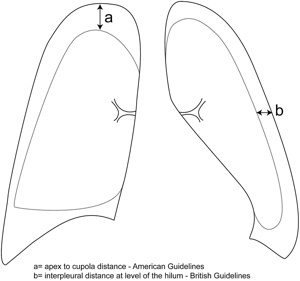

- Size of Pneumothorax - For the purposes of the current guidelines, "small" is regarded as a pneumothorax of a rim of air <2 cm and "large" as a pneumothorax of > 2 cm.

- High resolution CT scan is becoming used for management and decisions on best place to place drain in complex cases and in detecting small pneumothoraxes and differentiating pneumothorax from bullae. Also the scanners are now much faster and a scan can be done in under a minute.

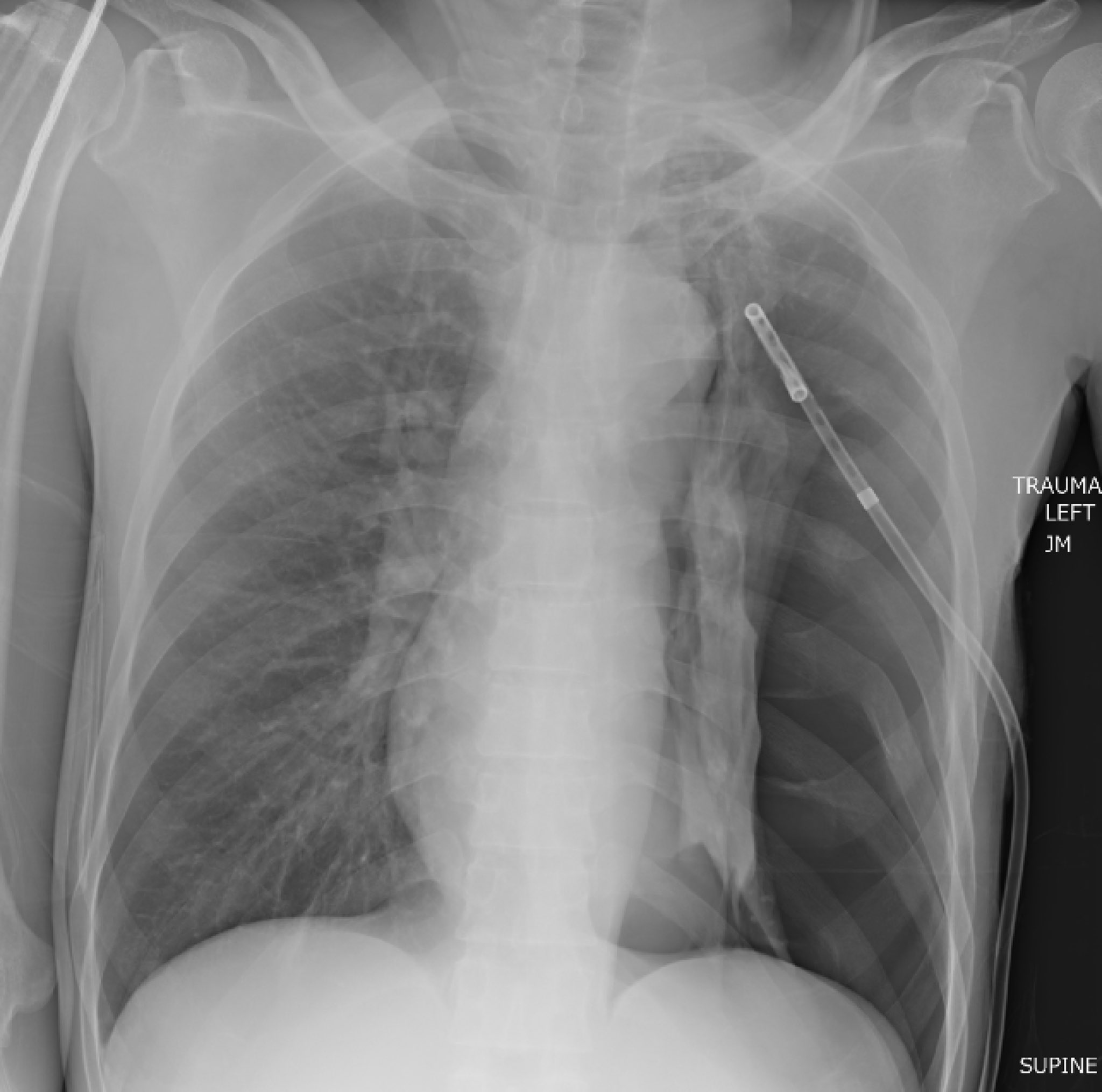

Left sided PTX with drain placed and possible blocked needing repositioned

Differential

- Bullous Disease: Do not confuse a large bulla with a pneumothorax: old CXRs on PACS archive may help. If in doubt, discuss with a radiologist and obtain a chest CT prior to drain insertion if appropriate.

Simple Aspiration

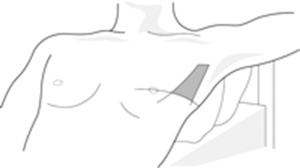

- Explain and obtain consent. Use sterile gloves. Sterile field.

- Infiltrate with Lidocaine 5-10 ml down to pleura in 2nd ICS in MCL or use the safety triangle. Aspirate air with a green needle.

- Use a 16 FG cannula (or less) at least 3 cm long. Insert at 90 degrees to the skin. Advance plastic cannula to hilt

- Once in pleural space, begin and remove needle as soon as tip within chest space.

- Connect cannula via three-way tap to the chest, 50 mL syringe.

- Aspirate and expel the air until resistance is felt, or patient coughs or complains of discomfort, or when 2.5 L aspirated.

- Remove cannula and apply a dressing. Repeat CXR to see if partially re-expanded and assess the clinical state

Indications for Chest drain in Spontaneous Pneumothorax

- Large (> 2 cm) symptomatic Primary Pneumothorax, after failed aspiration

- Large (>2 cm) Secondary Pneumothorax

- 1-2 cm Symptomatic Secondary Pneumothorax, after failed aspiration (If shallow pneumothorax may need CT guided drain).

- Pneumothorax of any size in a ventilated patient

- Tension Pneumothorax

- Bilateral pneumothorax.

Management

- ABC. Oxygen 15L/min (caution if COPD) as this helps by a factor of four. Ensure adequate analgesia if the pain is an issue.

- No evidence that large chest drains are more effective except in trauma. Smaller drains (e.g. = 16 Fr) are easier to insert and better tolerated by the patient.

- Those with chest drains best managed in a ward used to dealing with them (e.g. respiratory ward) to minimise complications.

- Failure to respond to treatment within 48 hours, needs respiratory physician consult.

- Get an HRCT if needed to help differentiate PTX from bullous disease, where PTX complex and drain placement is difficult e.g. partial adherence of lung to the chest wall or Incorrect tube placement is suspected or CXR obscured by surgical emphysema.

- Primary Pneumothorax (Age < 50, No lung disease)

- If <2 cm and not breathless: consider discharge. Referral to chest clinic in 2 weeks. Advise return to ED immediately if more breathless or chest pain. In meantime NO diving NO flying and NO smoking. Document this.

- If Breathless and/or PTX >2 cm rim on CXR: Aspirate. If still unsuccessful: insert the intercostal drain

- Secondary Pneumothorax (Age > 50, Smoker/lung disease)

- All require admission overnight for next day review and High flow oxygen unless COPD

- If 1-2 cm: Aspirate and if now < 1 cm give Oxygen and keep overnight for review next day.

- If 1-2 cm: Aspirate and if no change or worse then Chest drain 8-14 French and admit and give oxygen

- If > 2 cm or breathless the Chest drain 8-14 French and admit and give oxygen

- Air will continue to leak into the pleural space until the bleb has sealed and closed. With a chest drain in any pleural air is expelled on inspiration through the one-way system and the drain will bubble when the patient is asked to cough. The swinging of the drain just reflects intra-pleural pressures and shows that the tube is not blocked. A bubbling chest drain should never be clamped.

- The administration of supplemental oxygen e.g. 100% accelerates the rate of pleural air absorption and can be given as long as the patient is hospitalized as the absence of Nitrogen will lower the partial pressures and greatly improve the diffusion gradient

- Persistent bubbling on coughing suggests discussion with the thoracic team and thoracic surgeons as a bronchopleural fistula may have formed and the patient may require video-assisted thorascopic surgery (VATS) to repair any persistent leak. Once the bleb has sealed and air has to stop accumulating in the pleural space the drain should be removed. A repeat CXR should be done. Removing the drain - remove the suture holding the chest drain in place, withdraw the tube while the patient holds their breath in full inspiration. Use the two remaining sutures to seal the wound.

- Patients discharged without intervention should avoid air travel until a CXR has confirmed resolution of the PTX and many airlines will want a gap of 6 weeks between a resolved PTX and flying. If no intervention is necessary then there is a risk of recurrence for up to 1 year. Diving should be permanently avoided after a PTX unless the patient has had a bilateral surgical pleurodesis

- Pleurodesis may be chemical using tetracycline or talc which induces an inflammatory reaction in the pleural space causing the pleural and visceral pleural to fuse. Alternatively, bilateral surgical pleurectomy can be undertaken.